Warning: Use of undefined constant wpurl - assumed 'wpurl' (this will throw an Error in a future version of PHP) in /home/y9gq09f5yym1/public_html/wp-content/plugins/add-to-facebook-plugin/addtofacebook.php on line 50

As a longtime fan of Daniel Lanois, the now-legendary producer and guitarist, I am pleased to recommend his recent autobiography Soul Mining: A Musical Life

. The book is so detailed and revealing of how he helped create some of the best music of our generation, it should be required reading for anyone looking to be part of the creative process.

While much of the book is dedicated to telling the story of famous productions such as Bob Dylan’s “Oh Mercy,” U2‘s “Unforgettable Fire” and his nomadic career pattern, it is the relationship with his brother Bob that was most pivotal. It was he that was Danny’s constant partner in creating the studio in their mom’s basement which led to building a reputation in Toronto strong enough that Brian Eno came looking for them. As young Lanois held numerous jobs including meat grinder, gardener, pinsetter, caddy and paperboy, he and his brother applied hard work and ingenuity to their developing venture in the basement. In a particularly hopeless period, he played a series of gigs at Bobby Orr’s Ontario-based pizza parlor chain. When he met Eno, the man’s philosophy had a similar effect on young Lanois as it did for me reading it in a secondary source – “find something you love and jump into the arena.”

Keys to Creative Innovation

What talents are necessary to be a great record producer? Technical skill and ability to get the most out of any situation. As Lanois explains, he tries to “bring something to the table.” In fact, he hits several recurring themes for innovation throughout the book: intensity and ability to concentrate on a project; a deep fascination with speaker placement as well as meticulous analysis of his equipment and choosing instruments; the ability to self-criticize while considering improvements; he never hesitates to explore something that interests him deeply, “trusting it will find a home.” Lanois also believes that limitations are valuable in helping innovation, such as small units (3 people – a triangle is his favorite) or only allowing 15 minutes to do a mix. He is also an intense note-taker and says documentation and history provide choices. He could be running a technology company, but aren’t we glad he made it as a producer? His “summing amplifier” and preference for a “one-point source” are foundational ideas as well.

Listening to his productions and solo albums, having met the man and seen him perform numerous times, there was a lot I was interested in hearing about, but Lanois left in plenty of one of his favorite ideas, mystery. At one point, he even stops himself when describing various reverbs and techniques, saying he doesn’t want to give his secrets away. Who would’ve guessed he liked The Fat Boys though? He (accurately) refers to them as “a rare and inventive trio”! His early experiences recording everything left him open to everything too. Take a trip with him to Mexico and hear how the bells inspire him.

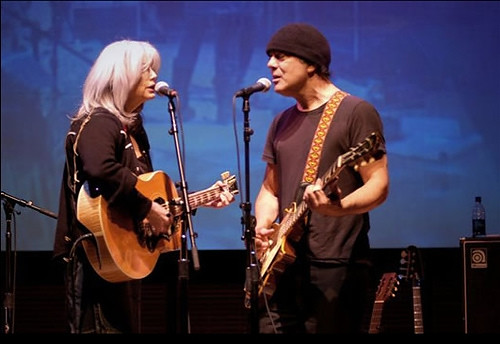

There’s no danger of anyone imitating Daniel Lanois as a producer or musician – he knows way more than could be gleaned off a page. How about he has recorded with Rick James, Raffi and Ne-Yo? He never mentions much detail in his personal life but a lot of us felt serious electricity when he worked with Emmylou Harris. Also left out of the book is his current project, Black Dub, although the background for it is clear – he was deeply involved with its singer’s father, Chris Whitley. The new band Black Dub is what Lanois “brought something to the table” for Chris’ daughter Trixie to begin her career with, a familar role but with a generational twist.

For example, a few technical highlights include his analysis that New Orleans’ humid air is a “loyal, relentless conductor of tone.” He doesn’t like equipment with noisy cooling fans, and constantly details speaker placement. Running in to the man at the Hollywood Bowl, he was impressed with their graduated speaker columns set at 15 row intervals up through the amphitheater. I wanted to talk to him about the Bugs Bunny episode that takes place there. But I also told him at one point that “Series of Dreams” was a great song, and its deletion from “Oh Mercy” still has him indecisive.

Coincidentally, this was one of three relatively subtle typos I found in the book. He says the song was included on a bootleg, but all Dylan fans know that should have been capitalized, since The Bootleg Series Vol. 1-3 is where the song appeared. Lanois also refers to Bob Marley in a list of incredible bass players, but I’m sure he knows the name Aston “Familyman” Barrett, the bassist in the Wailers. I wonder if his friendship with Chris Blackwell made him eliminate the controversial character’s name, but there is also a reference to “Stand Up for Your Rights,” not “Get Up Stand Up,” the song’s actual title. Apparently Faber and Faber are not that locked in!

He doesn’t dish on Robbie Robertson, but clearly it was a negative experience recording the self-titled 1988 comeback with the famous leader of The Band, and a Canadian music icon he may respect too much. Robertson is one charismatic guy, but his nettlesome project interrupted the recording of The Joshua Tree and a few other big albums. Also, the way Lanois refers to Levon Helm and Garth Hudson is distinctly different from his calling Robbie “a buddy” – a personal and not a professional estimation. He describes editing the good parts together with so much effort that “I became tape.” After all this, some schmuck at Geffen, probably not the “Gersh” who came to assist Lanois when trespassers show up in his LA home years later, had Bob Clearmountain mix the Robertson album. He’s pissed and I can tell (to paraphrase the great Willie).

Of course, one of my peaks as a fan of Lanois was promoting Teatro, my first project with Willie Nelson, and Lanois saves this four-day story to the end of the book. Willie’s place in his heart is obvious – he refers to a Christmas in Ontario where they “only had one record to listen to” and it was his. The inclusion of five pictures of the Nelson session where Dylan, Bono and a few others get one seems significant too.

I also appreciate his perspective on people in the music business, who “carry the torch while I sleep” and his workaholic level of responsibility for his projects.

“The world loves a record that is specific in its stance.” It’s not a coincidence that some of Daniel Lanois’ best songs as a solo artist reflect his deep, spiritual commitment to making music. Jerry Garcia, Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris all covered “The Maker” – that has to bring him some joy. Another important one asks, “Where Will I Be (when my time comes)?”

I could go on for days about Daniel Lanois. His music has made a big difference in mine and many people’s lives.