Warning: Use of undefined constant wpurl - assumed 'wpurl' (this will throw an Error in a future version of PHP) in /home/y9gq09f5yym1/public_html/wp-content/plugins/add-to-facebook-plugin/addtofacebook.php on line 50

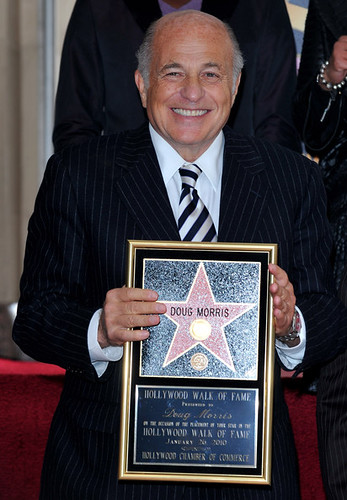

In the negative atmosphere produced by Matsushita‘s takeover of MCA, which it had acquired 5-6 years earlier, Edgar Bronfman and Seagram’s purchased the conglomerate and re-named it Universal in the late 90s. A short time later, Bronfman, who had re-named the company Universal, after the film company MCA purchased in the mid 50s, closed a deal with Doug Morris to purchase PolyGram Holdings Inc. from its parent, Dutch appliance and electronics manufacturer, Phillips, reducing the number of “major labels” from 6 to 5.

The merged company was immediately A LOT bigger than its competitors. No one had ever seen a label so large and so packed with superstar artists, and Universal is still on top a decade later. I was there and I believe it was a brilliant deal for the label, but maybe not for the workers or artists who were forced out.

“The Sweetest Thing”

Over the summer of 1998, Johnny Barbis led the Island staff on a charge up the charts for U2‘s Greatest Hits 1980-1990‘s single, the b-side (to “Where the Streets Have No Name”) “The Sweetest Thing.” As the song crested in the fall, U2 announced their future albums would come out on Interscope, the label run by Jimmy Iovine.

The staff was asked to re-apply for their jobs by interviewing with the new bosses, as a significant change in department heads had taken place over the summer. Attrition continued but in general the fall release schedule by PolyGram labels Island, A&M, Mercury and Def Jam was proceeding, as it was on the Universal side with Geffen, Dreamworks, MCA Records and Motown, along with countless “boutique” spinoff/joint ventures such as Outpost, Almo, London, a massive Jazz and Classics (ECM, Deutsche Grammophon) operation with PolyGram and a deep reissue department on both sides.

In the year prior to the merger, Mercury Records, headed by Danny Goldberg, supposedly had released 248 records via all its deals and side projects! One of Mercury’s few profitable artists was Shania Twain, who had her breakthrough that year.

A new set of executives

Soon, Jim Caparro, who had been head of PolyGram Distribution, was announced as CEO of Island Mercury, which would be the east coast based operation, and on December 15, 1998, Jim spoke to the combined staffs of Island and Mercury, who had been working records alongside each other late in the fall. The meeting took place at the Hudson Theatre, and the tension was palpable as none of us knew what was going to take place.

The last PolyGram holiday party took place at the Kit Kat Club, a Times Square dance palace/old guard theatre that used to be Xenon in the 70s/80s. That added to the already-Maudlin atmosphere during which Jan Timmer, Alain Levy and Roger Ames, the heads of the company which had been sold out from under them, mingled with their former employees in a daze. PolyGram had a European-influenced culture, and people liked working there even if it was less than competitive sometimes.

At the Hudson Theatre, Caparro outlined the future of the company: an intense focus on fewer releases; a “fanatical” approach to your own job, in which you demanded the company’s “unequal fair share” of the marketplace and an atmosphere of accountability. Based on these criteria, Caparro said he would decide who the staff would be in the future.

The projects I had promoted in 1998 had done exceptionally well, and with Island’s concentration of talent in the underground/developing genres I was responsible for (techno, reggae, indie, etc. and there was a lot of etc.) would hopefully put me in good standing compared to the Mercury rep, but Mercury’s folks (David Leach, Steve Ellis, etc.) were in charge of promotion, and only a handful of Island employees would be kept.

There had also been the matter of a pissing match over the band Pee-Shy, whose album DJ Shadow (an Island-London artist) kept from going number one in CMJ. I had been working Tricky (Angels with Dirty Faces), PJ Harvey (Is This Desire?) and Willie Nelson (Teatro), albums that had all over-performed.

I had gone on the road with Angelique Kidjo, I hooked Spring Heel Jack up with Lee Perry, I… worked albums that sold like 4000 copies. It was a toss-up and Johnny Barbis confirmed this for me when he explained that my job was a “luxury” for the company.

We were appropriately scared as we began to “re-apply” for our jobs and broke for the holidays at the end of 1998. On January 15, 1999, a gutting of the combined companies would take place that we see A&M, Geffen, Almo, Outpost, Dreamworks and MCA made part of Interscope Records; Def Jam, Mercury and Island combined to form Island Def Jam; and Universal, Motown and Republic shortened to Universal Records. Or something like that.

The afternoon prior, the staff received a letter inviting you to either an 11am or 2pm meeting the next day. If you were in the early meeting, a company HR person explained that there were boxes and bubble wrap being put in your offices now, and this is it, do you have any questions. There were about 40 people fired at a time.

At the later meeting, it was more like a stunned silence as a semblance of business as usual carried out with new staff positions being announced and a review of upcoming releases was discussed. Caparro’s first projects under the new regime would be The Cranberries “Bury the Hatchet”; The Bosstones; Pound, a local New York rock band; The Insane Clown Posse, plus follow up singles from artists like Susan Tedeschi, Rammstein, Melissa Etheridge and Lucinda Williams.

Suddenly, Lyor Cohen and Def Jam came into the picture and Island Mercury became Island Def Jam instead, and the roster and office staff had an injection of talent that was utterly transformational. John Reid had been hired as President of Island Mercury, and had come from PolyGram Canada with Livia Tortella, an extremely conscientious marketing person. His sponsorship of Shelby Lynne and Sum 41 would be his best acts in office, while Jay-Z and DMX approached their commercial and creative peaks, Ja Rule, Def Jam dominated the culture of the company.

With Napster and other file sharing webpages raging full on, even tougher times were ahead for the music business and its workers, but January 15, 1999 was the first blow of technology against the “old model.” The new company would put release only the most commercially viable projects, every single cost and promotional idea was dissected, and a certain amount of “tension” spiced the atmosphere (as well as loud music and joy for still having a job).

State of the industry 2008/09:

Other Major Labels: BMG and Sony merged; EMI sold to Terra Firma Partners after losing Radiohead, Paul McCartney and The Beatles catalog; Warner/Elektra/Atlantic purchased by Lyor Cohen and Edgar Bronfman, who both left Universal as soon as his five year deal ended in 2004. The new Warner Music Group boasts digital sales higher than physical, either a breakthrough or brilliant spin.

Retail: Borders and Barnes and Noble the only “brick and mortar” national retailers, Starbuck’s strength peaks with Paul McCartney signing, disbands music division a year later.

Effects of Napster and iTunes/iPod

Digital theft into ecommerce, with iTunes and phones. Pod capped the gusher Doug Morris, Edgar Bronfman and (later) Jean-Marie Messier envisioned, and phones have also been proven as a distribution service for full songs, ringtones and then “ringles.”

They were right conceptually (vertically integrating music properties with technology/distribution systems), but the company was too heavily leveraged by Messier to wait a few more years for that to become a business. In 2002, “JM2” was forced out after nearly bankrupting the company on acquisitions like Canal Plus, Activision and many other companies. He also bought a $10m+ townhouse for his personal use in New York and was generally abhorrent in the press. Vivendi subsequently sold off Seagram’s liquor to Diageo and Universal’s vast TV and Film library to NBC.

I’m glad my hero, the great Lew Wasserman, who built MCA through brilliant acquisitions like Decca Records, didn’t live to witness most of this nightmare, especially since a lot of folks think he and Sid Sheinberg left the company vulnerable to the Matsushita takeover in 1990. For greater details about the most powerful executive in the history of show business (and possibly any business), I strongly recommend the Lew Wasserman bios The Last Mogul and When Hollywood Had A King, and the DVD documentary, The Last Mogul. Lew Wasserman was the man if ever there was one!

But it’s one thing to read a book about it, it’s another to live through it. My thoughts are with all American workers having a tough time due to mergers, acquisitions, and all other forms of corporate massive attacks on the people who keep them going.

The Universal-Polygram merger was death for the 2nd Hempilation, which came out in ’98. They distributed it via Capricorn. It totally got lost in the shuffle and despite having Willie, Watt, George Clinton, Wayne Kramer, Spearhead and many more on the cd, it tanked, selling just 25K. The first Hempilation, distributed by RED in ’95, sold over 125K. So (I co-produced both cds – they benefitted NORML.) So I’ll always have a little grudge against Universal and the merger.

As one of hundreds of A&M employees who lost their jobs, and witnessed the demise of one of the great brands and most rewarding record company cultures to ever grace the music business, the Polygram sale still stings, a whole decade later. But the sale obviously showed some (surely largely incidental) foresight of the music business downturn just ahead – not least from Philips, who were wise enough to cash out of the music business before the shit hit the fan.